The culture we’re raised within is created by the customs we practice and the beliefs we hold. Our culture influences how we see and interpret the world around us. Awareness and appreciation for cultural differences build more understanding and empathy toward our fellow man. It is one of the most incredible benefits of traveling abroad. I have found that the most problematic sects of our society are those who are cut off from the world, never leaving the confines of their culture and, therefore, threatened by outside influences.

Twenty-one days into a trip around the world, I am constantly adjusting to cultural differences and learning new local customs. Personally, I find performing everyday tasks in new ways fascinating. In many instances, I discover a better way of doing something; in others, I may walk away frustrated or humbled by the false assumptions I brought into a situation. In either instance, constant flexibility is vital.

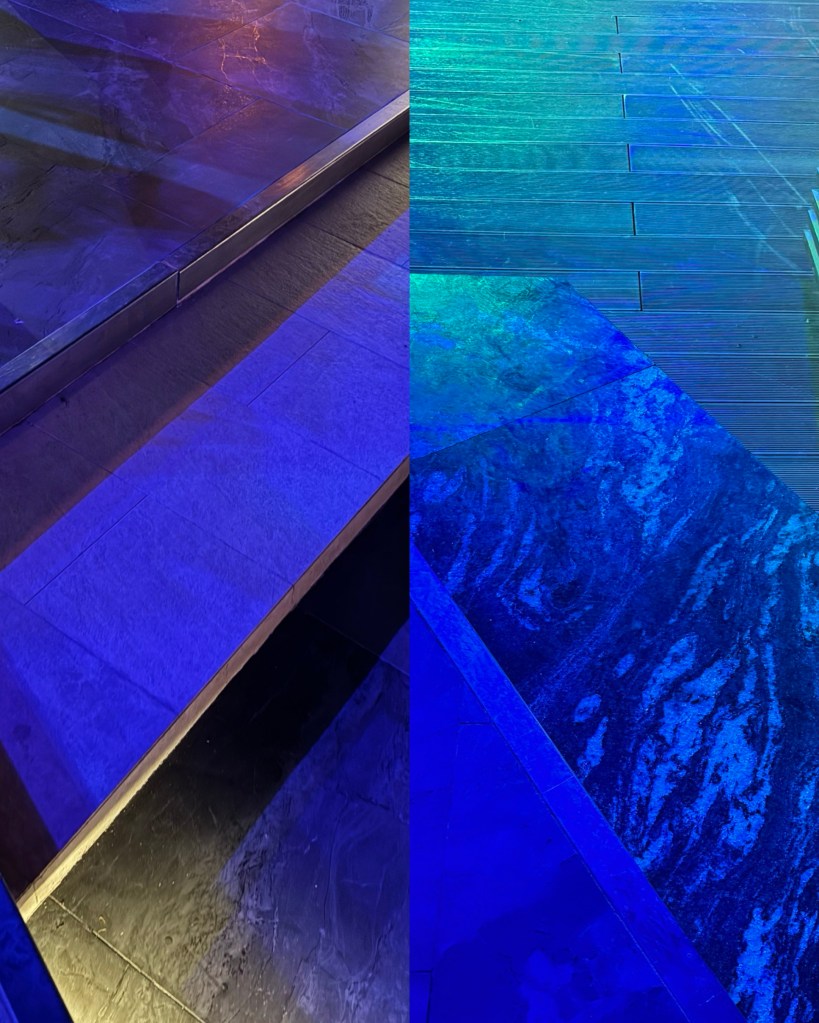

Design element or population control?

For example, I discovered a subtle but life-threatening local design custom in Asia. I can only guess that for population control, Asian design calls for small elevation changes to distinguish different areas within a space. This big toe killer comes in the form of small steps no more than three or four inches in height. There will be raised and lowered elevations within the same area; it’s never just one direction of inclination or decline. I’ve found that designers further seal your fate by introducing intense mood lighting that casts shadows, easily camouflaging said steps. These death traps are handy in restrooms — they’re used going into showers, exiting toilet stalls, or approaching wash sinks — basically on the worst floors, you would want to meet face to face. These observations were confirmed as I witnessed my travel companions staring intently at the floor, gingerly navigating across rooms. We started calling out elevation changes to one another so that no one would break their neck or, worse, spill a martini. Unfortunately, even walking the streets presented a different life or death custom to adjust to — driving on the left side.

Walking the thin line between life and death

A simple thing like crossing the road could have severe consequences for someone who is unfocused. In America, we’re accustomed to navigating from the right side of the road or sidewalk; it’s how we operate and deeply engrained into our “default” mode. They drive and walk to the left in two of the three countries I’ve visited so far. If I’m not careful, I could find myself kissing a bus or scooter.

If I’m not careful, I could find myself kissing a bus, car, or scooter

According to my fitness tracker, I walk five or six miles daily. I prefer to walk over ride-shares or public transportation because you see and experience so much more on foot. When in a car or train, streets change quickly, and places of interest are just a blur. You quickly lose your sense of direction and where you are on the map. And I miss the sounds and smells of a place that will intensify the memory and recall of your travels. My rule is that I go on foot if it is less than a thirty-minute walk. I’ve found this distance to be the sweet spot between wait times for getting to and waiting on trains and the time it would take to just walk it. Plus, you have the added benefit of exercise, and we all know that vacation pounds can pack on quickly. Walking this much, your mind often wanders — observing your surroundings or reflecting on your day’s experiences. Suddenly, you find yourself back in “default” mode as you check for oncoming traffic, looking left instead of right. Stepping out into what you think is a clear path could be met with dire and deadly results. As such, I have implemented a no-break rule to cross streets using the pedestrian signal. Even when there is no traffic and a bolt across the street is a practical and efficient approach, I wait.

There are so many other examples of new customs I’ve experienced over the last couple of months. I thought I would share a few examples of local practices that required me to think or react differently.

Don’t flush toilet paper in Belize.

Like in Belize, you cannot flush toilet paper; their plumbing and water pressure are so fragile that you can easily clog the pipes and create serious property issues. You must put your used toilet paper in small trash bins beside the toilet – ewww! This is incredibly uncomfortable when sharing a room with a friend. I don’t want to see that or share that! I was so stressed about performing this new custom that I did number two in the resort restaurant bathroom for the first three days. My thought was at least my used paper would become anonymous in the bin. But, after several visits, I got tired of the trek, and I think the wait staff picked up on the practice.

Keep your feet on the ground in Thailand.

In Asia, I had to be careful not to deeply offend locals with my shoes and feet. In that culture, the bottom of the feet or shoe is the dirtiest part of a person, touching the grime and filth on the ground. So, pointing the sole of your feet or shoe toward someone is very offensive. That’s why you remove shoes when entering a home. But you must also be careful not to point the bottom of your shoe toward someone when crossing your legs. I constantly adjusted how I sat to cross my legs at the knee versus across the knee as usual. I learned that in Thailand if you were to accidentally step on currency, you are illegally defiling the King whose face is on each bill. In theory, you could go to jail.

Cambodia takes money laundering to a new level.

Speaking of Kings and currency, in Thailand and Cambodia, cash is King. Using a credit card to pay is frowned upon, so you must keep a wallet full of currency, hopefully in small denominations, so you can tip without asking to break a bill. In Cambodia, they forgo their own riel, which is so inflated that you must carry bills in the hundreds of thousands range. They prefer to use the US dollar to simplify things and protect themselves from lost value. But not just any dollar will do; they carefully inspect each bill for marks, tears, or any type of wear. As a matter of fact, my parents gave me two crisp $100 bills for Christmas that I knew would be perfect to use on the trip. On my last day, the only currency I had left was a single $100 bill, so I went to the hotel front desk and asked for change to make it easier to transact. The desk clerk inspected it thoroughly, holding it to the light and turning it over and sideways. She returned it and said, “I’m sorry, we can’t accept this bill.” Since this was the last of my cash, I frustratingly said, “Why not? It’s a brand-new bill and the last bit of money I have.” She then pointed out a deposit stamp on the bill, which makes it useless in Cambodia. Damn you, Bank of America! I went to the ATM, praying my bank allowed transactions in Cambodia; otherwise, I didn’t know how to pay for the one-hour transport to the airport. Luckily, it went through, and I got a change for the car service. If you visit Cambodia, bringing stacks of perfect cash in small denominations will make things work so much easier.

Sticky fingers in Bangkok

Another odd Asian custom is their use of napkins. Most restaurants had small napkin dispensers on the table, unlike what you’d see in an American diner. They were more like the small travel dispenser you would keep in your purse or briefcase. The napkins were about the size and thickness of a single square of toilet paper. As a messy eater, I would collect a pile of tissue around my plate. I would also find remnants of tissue stuck all over my fingers — who knows how much tissue I accidentally ate. I wonder why they don’t use thicker paper? Maybe it forces people to eat with chopsticks or utensils rather than hands? Who knows? All I can say is that I appreciate Australia’s big and thick napkins.

This isn’t Starbucks, mate.

I’ve been ordering at cafes wrong all this time. I went to the counter and ordered a long black (large coffee) and a toastie (breakfast sandwich). The server asked, “What table number?” I said, “I don’t have a table yet.” She then asked, “So you want takeaway?” “No, I’ll eat it here,” I replied. “And where will you be sitting?” she asked. In a frustrated tone, I said, “I don’t know yet, perhaps a table in the shade?” It went on and on, and a line of customers started to form behind me. Finally, a server took me outside to find a table and took my order. You see, I thought Australian cafes operated like an American Starbucks. You go to the counter, order your coffee, then fight for an open seat. Here, you find a seat, order at the counter with your table number, or wait for someone to take your order. As a solo traveler, it can be a bit of a challenge to hold a table without being at the table, so you have to claim it with a personal item. But I’ve learned not to be afraid to ask dumb questions. It’s much better to admit ignorance to a new custom rather than suffer the confusion and make an ass of yourself.

Charging up is a two-step process.

I’ve noticed Australians have an obsession with electrical safety. I find this so odd for a first-world country. Every outlet has its own on/off switch. So, plugging something in doesn’t necessarily send power down the cord; it’s a two-step process. In addition to plugging your US adapter into the outlet, you must also find and turn on the outlet’s switch. In America, we only do this to control the outlets used for lamps from the switch near the door. But, in Australia, it’s every freaking outlet. I learned this the hard way when charging my phone overnight. The following day, I was dead in the water when I realized I hadn’t flipped the switch to charge my phone. Let’s just say my reliance on my phone during travel delayed the start of my day. They take this safety feature so seriously that housekeeping turns off every outlet during daily cleaning.

The big takeaway

Learning how people approach similar activities differently is the most exciting and beneficial aspect of traveling abroad. The benefits of crossing into new cultures aren’t limited to international travel but within our home country. It’s the small-town girl visiting the big city and vice versa. It’s the West Coast boy seeing life on the East Coast, the mentorship between people of differing faiths and races. The simple truth is that it is more difficult to hate a group or culture if you have just one friend within it. Over 75% of the world’s population have never traveled outside their home country, and 68% of people also stay in the city they were born. What would the world be like if this statistic were reversed?

Leave a comment